RACINE & PEWAUKEE WISCONSIN

|

SMART goals are an essential part of the performance management routine. They guide and align our ambitions to an objective and verifiable standard. However, SMART goals have one fundamental flaw that can stifle growth and development. Just because a goal is SMART, doesn’t mean you will be SMART. Could I propose an alternative? How about SMART-ER goals?

If the narrow-minded purpose behind goal setting is some variation of “practice makes perfect,” then SMART goals will suffice. But if goal setting has a more ambitious aim, perhaps growth, performance, or development, then SMARTER goals need to prevail. What is a SMARTER goal? Just add the “ER” to any objective and ask, “Is Education Required?” If you don’t have to learn something to accomplish a goal, then you are simply honing already developed skills. How about setting goals that require you to learn something before you can accomplish the objective? Set goals that force you to look something up, speak with someone more expert than yourself, watch a short video clip from one of the masters in your craft, or maybe, read a book. SMART goals are self-deceptive as they only demand that we make our goals clear and reachable. How about being SMARTER and make those goals just a bit beyond your reach? Build in a learning challenge and stretch yourself. SMART goals are about effort; SMARTER goals are about performance. Confusing effort and performance is a strategic error. It’s like putting your car into neutral and revving the engine – lots of sound and fury, but you don’t end up anywhere different. Next time you’re setting a goal, put your energy into gear, demand that you learn something, and make your goal SMARTER. If getting a yes is an inside-out process (see Part I), giving a yes can be equally complicated.

You remember the scenario – the resistant child finally acquiesces to the multiple demands of the parent to sit down, but defiantly mumbles, “Ok, but on the inside, I’m standing up!” We’ve all been there; saying yes when you want to say no. So, what about the child in all of us who wants to stand up when we're supposed to be sitting down? Saying yes when we mean no, disrupts our internal equilibrium and sends a mixed message to those around us. No matter how well we think we can hide the incongruence, it leaks out. Without realizing it, the double message seeds doubt and mistrust in the mind of the hearer, potentially undermining relationships. So why do we say yes when we mean no, and what can we do about it? The Yes Person For some, “yes” is a knee-jerk response triggered by a need to please. The consequence of automatically saying “yes” to every request is that it sabotages all hope of timely follow-through. Saying “yes” when you really should say “no” leads to over-commitment and under-delivery. Ironically, the yes person becomes a displeasing source of frustration and annoyance – the very thing that saying “yes” was supposed to prevent. The Team Player Sometimes we say “yes” instead of “no” because we want to be seen as a team player. While the motivation is admirable, the strategy is flawed and does little to promote real teamwork. Conflict (saying no) is critical to team success. As I often say to couples I counsel, “If two people agree on everything, then one of them is unnecessary.” It’s a “ditto” relationship and creates a weak partnership. The same applies to work teams. Conflicting opinions and ideas are a rich, but seldom tapped, resource for teams simply because conflict is difficult and often avoided. Saying “yes” when you mean “no” avoids conflict but limits team effectiveness. But before you jump to a resounding “NO!” could I suggest that we begin with a sincere “why”? Asking Why? Asking "why" can be either a passive-aggressive challenge or a bid for understanding. It is the latter that fosters clarity and collaboration. Knowing why you're asking why is an inside issue, so analyze your motivation first, then proceed humbly. The sequence is "yes," followed by an inquisitive "why." It might sound something like, "Sure, glad to…. Wondering if you could help me with some context so I can fully understand what you're looking for?" Asking "why" is one of the contributions of effective followership. Hopefully, your manager just wants a "yes," not a yes-person. Finding ways to creatively explore, understand or even critique the rationale behind the directive allows you to contribute to the problem-solving process. To do so requires tact and diplomacy. Like adding salt or spice to an already prepared dish, it needs to be applied judiciously. And sometimes, you just need to sit down. The scenario is an encounter between parent and child, but it has practical ramifications for every leader. "Sit down," says the parent. "No" comes the reflexive response of the suddenly not so cute three year old. "I told you, sit down!" "Why?" The child retorts. "Because I said so!" comes the redundant response. Unimpressed by the rationale, another "No" defiantly follows. "Sit down or you'll be in trouble" comes the more sternly worded directive. This time the "No" is not quite so confident. "Sit down or I'll take away your (fill in the child's most precious possession). Now, sensing this might actually be serious, the child complies, but retorts, "OK, I'll sit down, but on the inside I'm standing up." The adult version of this exchange plays itself out repeatedly in the workplace. What manager hasn't sensed a similar dilemma with their employees? You may ultimately get compliance, but there's that nagging doubt that someone's not all in. You finally get the "yes," but the performance that follows is lackluster, inconsistent and quickly fades without constant prodding and directing. Why? Because getting a yes requires an inside-out strategy. Or perhaps you've been on the other end of the conversation. You are being required to do things one way, and you resist. Eventually, you are worn down and comply, but suddenly work is just harder, energy sputters, passion evaporates. Why? Because giving a yes requires an inside-out strategy. For the parent-manger in you, here are a couple of thoughts to ponder. First, threats don't work long term, and repeated threats without follow through serve only to undermine your credibility. Second, directives are best received when paired with context. The automatic “why” offered by a resistant child is not always an expression of rebellion; for some, it is a legitimate request for understanding. The same is true for our direct reports. When we to elaborate on the reasoning behind our requests, receptivity is often enhanced. Typically, it is in the context (or more accurately the perceived context) where we find the genesis of the power-struggle. Getting context out in the open is a great first step in revealing unspoken conflict. Requests coupled with a contextual frame invite dialogue, discussion, and even disagreement. However, most managers prefer not to share the rationale behind their directives because doing so provides potential data for debate and resistance. But then again, is the goal compliance or buy-in? Of course, be sure to discern when the exploration of creative options is advantageous, and when it is counterproductive. Again, the issue is whether you want an outside yes, or an inside yes. Are those you lead healthy followers, or do you just want "follower-sheep?" Rationale also needs to be aligned with purpose. Daniel Pink in his book Drive, expands on the importance of "why" when he states: "In business, we tend to obsess over the 'how'-as in 'Here's how to do it.' Yet we rarely discuss the 'why'-as in 'Here's why we're doing it.' But it's often difficult to do something exceptionally well if we don't know the reasons we're doing it in the first place." Commands may bring compliance, but context brings cooperation. If you want cooperation, work the inside, not the outside.

And what about the child in all of us who wants to stand up when we’re supposed to be siting down? That’s Part II. A sad, but inevitable hazard of leadership is that you often find yourself in “The Pit.”

You may have fallen, or been pushed, but It’s a place of personal pain, heartache and confusion that is all too familiar to those in positions of responsibility. Some of the pain is self-inflicted, the rest is collateral damage from doing the work of leaders. The greatest wound of all comes from the betrayal of a close confidant, trusted staff or even a family member.

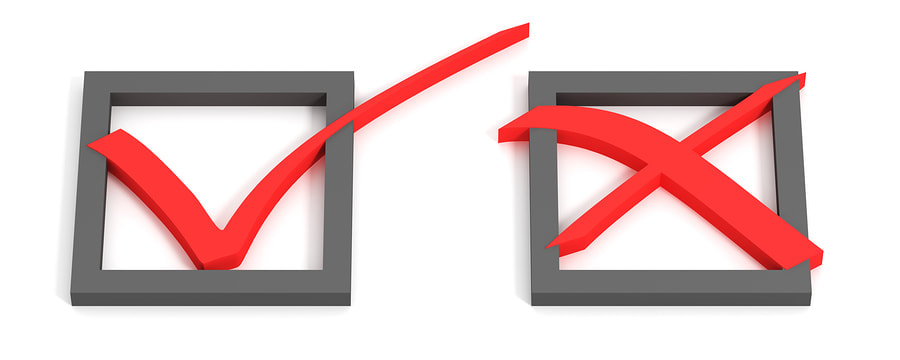

The journey out requires a request for help. Sadly, leaders often struggle with the very act of asking for assistance. Somehow to ask for help implies a double fault, as though such action confirms the failure. It’s a no-win scenario that leaves many leaders trapped. Those who are healthy (or desperate) enough to make the request, often turn to an expert, a consultant, a confidant, a mentor, who will help pull them out of the mire. But with a multitude of self-declared counselors, finding a trustworthy advisor can be a challenge. Consider the story of a traveler who’s fallen into a hole. As the victim struggles to get out, three people pass by and offer consultation. The first advisor begins with a detailed explanation of why the failure occurred, pointing out every misstep and ending with a stern admonition to avoid duplicating such errors in the future. But of course, that does little to free the victim. The second counselor rebukes the negativity of the first and offers a more positive solution. Shouting encouragement and affirmation from the edge of the precipice, he passionately exclaims, “You can do it, believe in yourself!” But still, the victim remains trapped. The final co-traveler, upon hearing the request for help, jumps into the deep pit and joins the frustrated victim. “Oh no! Why did you jump in? Now we’re both down here!“ exclaims the helpless victim. “Don’t worry,” comes the reply, “I’ve been here before and I know the way out.” Consultants come in many varieties. For the courageous leader who takes the step to get such help, choose wisely. 9/7/2020 THE ON PURPOSE LIFE[This is a portion of a commencement challenge delivered to both the 2016 graduating class of Shepherds College and Leadership Union Grove.] There are three elements of the OnPupose life I’d like to challenge you to embrace. They are reflected in the life of one of my heroes – Eric Liddell, or the “Flying Scotsman” as he was often called. Eric won a gold medal at the 1924 Paris Olympics, and part of his story was captured in the movie, Chariots of Fire. I was drawn to Eric Liddell for a couple of reasons. He was born in China, so was I. He was the child of missionaries, so was I. He attended British Schools, as did I. He was a superb athlete… oh well, 3 out of 4 isn't bad. I believe Eric Liddell lived life on purpose. I see it in three aspects of his life. I certainly try to emulate them; I hope you will too. Live Life INTENTIONALLY A life lived on purpose intentionally cuts away anything that does not align with the mission. Doing so requires some tough decisions. The hardest decision you will have to make as a leader will not be between good and bad, but between good and good. For you see, the enemy of what is best in your life is often something that is good. Clarity of purpose will help you choose the better good because it aligns with your purpose. Others may not understand, they may question, even ridicule your choice. But a life lived on purpose is lived INTENTIONALLY. Eric Liddell stuck by his convictions regardless of the cost. Consistent with his values he chose not to race on Sundays as he believed it was to be a day of rest. As a result, he could not qualify for his best event, the 200 meter. Instead, he ran the 400 meter and in spite of being an underdog, won in spectacular fashion. What others thought to be a mistake, ended up defining his legacy. He lived life intentionally. He made tough choices easily because he was clear on his purpose. Secondly, Live Life SACRIFICIALLY Many know of Eric Liddell's Olympic exploits, but what they fail to appreciate is the life he lived after the Olympics. Once the super bowl ring is slipped on the finger, once the trophy is raised in celebration, once the victory lap is complete, what happens next? Is that the pinnacle of a life’s achievement? After the Olympic Games in 1924, Eric Liddell returned to China and continued a life of sacrifice and service as a missionary and as an educator. When the war broke out, his family was sent to Canada, but he remained, teaching and ministering to the people he was called to serve. The Japanese occupation resulted in his imprisonment in an internment camp with other missionaries. He died there of a brain tumor in 1945, five months before the camp was liberated. At the recent games in Beijing, the Chinese government revealed that he had been offered a prisoner exchange, but he turned it down asking instead that a pregnant woman in the camp take his place. That’s a life lived on purpose, a life lived sacrificially. Lastly, Live Life PASSIONATELY If you’ve seen the movie you will know that Eric Liddell's running style was rather unique. Some would and did call it undignified. His arms would flail, his head arch back his mouth gaping open, not a pretty sight. But he was all in. There’s line in the movie that captures the essence of a life lived with Passion. Eric says, “God made me for a purpose, China. But He also made me fast, and when I run I feel his pleasure.” When you align your strengths with your purpose, you will experience a flow, a passion that will energize and propel you to the finish line. I want you to feel the pleasure of a life lived on purpose.

Live INTENTIONALLY Live SACRIFICIALLY Live PASSIONATELY. Thank you for the privilege of allowing me to use my strength to invest in your lives. It makes me feel His pleasure. |

Dr. Russ KinkadeDeveloping Leaders from the INSIDEOUT ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

9/7/2020

1 Comment